Wazstagram is a fun experiment with node.js on Windows Azure and the Instagram Realtime API. The project uses various services in Windows Azure to create a scalable window into Instagram traffic across multiple cities.

The code I used to build WAZSTAGRAM is under an MIT license, so feel free to learn and re-use the code.

How does it work

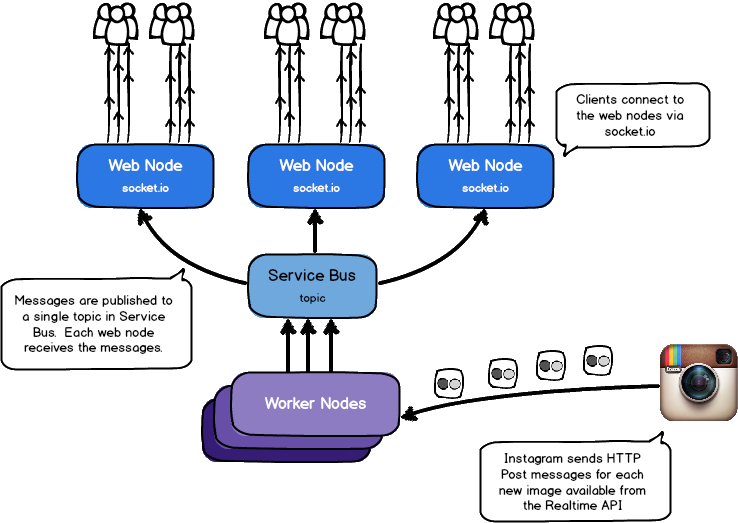

The application is written in node.js, using cloud services in Windows Azure. A scalable set of backend nodes receive messages from the Instagram Realtime API. Those messages are sent to the front end nodes using Windows Azure Service Bus. The front end nodes are running node.js with express and socket.io.

Websites, and Virtual Machines, and Cloud Services, Oh My

One of the first things you need to grok when using Windows Azure is the different options you have for your runtimes. Windows Azure supports three distinct models, which can be mixed and matched depending on what you’re trying to accomplish:

Websites

Websites in Windows Azure match a traditional PaaS model, when compared to something like Heroku or AppHarbor. They work with node.js, asp.net, and php. There is a free tier. You can use git to deploy, and they offer various scaling options. For an example of a real time node.js site that works well in the Website model, check out my TwitterMap example. I chose not to use Websites for this project because a.) websockets are currently not supported in our Website model, and b.) I want to be able to scale my back end processes independently of the front end processes. If you don’t have crazy enterprise architecture or scaling needs, Websites work great.

Virtual Machines

The Virtual Machine story in Windows Azure is pretty consistent with IaaS offerings in other clouds. You stand up a VM, you install an OS you like (yes, we support linux), and you take on the management of the host. This didn’t sound like a lot of fun to me because I can’t be trusted to install patches on my OS, and do other maintainency things.

Cloud Services

Cloud Services in Windows Azure are kind of a different animal. They provide a full Virtual Machine that is stateless - that means you never know when the VM is going to go away, and a new one will appear in it’s place. It’s interesting because it means you have to architect your app to not depend on stateful system resources pretty much from the start. It’s great for new apps that you’re writing to be scalable. The best part is that the OS is patched automagically, so there’s no OS maintenance. I chose this model because a.) we have some large scale needs, b.) we want separation of conerns with our worker nodes and web nodes, and c.) I can’t be bothered to maintain my own VMs.

Getting Started

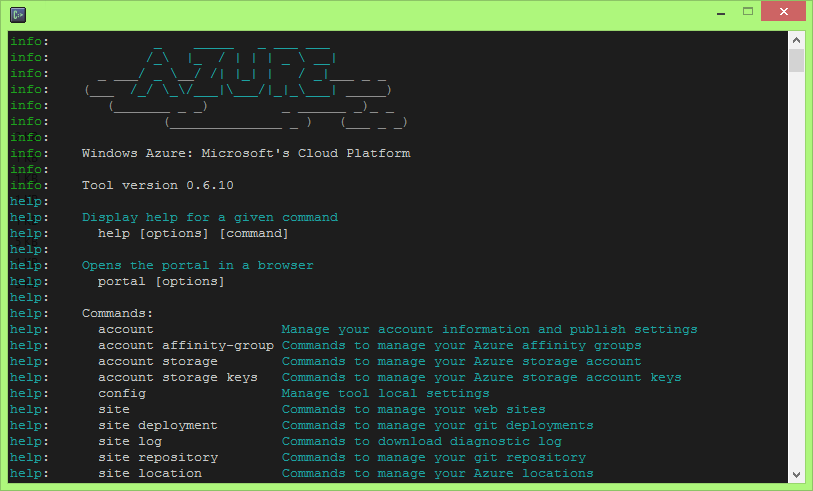

After picking your runtime model, the next thing you’ll need is some tools. Before we move ahead, you’ll need to sign up for an account. Next, get the command line tools. Windows Azure is a little different because we support two types of command line tools:

- PowerShell Cmdlets: these are great if you’re on Windows and dig the PowerShell thing.

- X-Platform CLI: this tool is interesting because it’s written in node, and is available as a node module. You can actually just

npm install -g azure-cliand start using this right away. It looks awesome, though I wish they had kept the flames that were in the first version.

For this project, I chose to use the PowerShell cmdlets. I went down this path because the Cloud Services stuff is not currently supported by the X-Platform CLI (I’m hoping this changes). If you’re on MacOS and want to use Cloud Services, you should check out git-azure. To bootstrap the project, I pretty much followed the ‘Build a Node.js Chat Application with Socket.IO on a Windows Azure Cloud Service’ tutorial. This will get all of your scaffolding set up.

My node.js editor - WebMatrix 2

After using the PowerShell cmdlets to scaffold my site, I used Microsoft WebMatrix to do the majority of the work. I am very biased towards WebMatrix, as I helped build the node.js experience in it last year. In a nutshell, it’s rad because it has a lot of good editors, and just works. Oh, and it has IntelliSense for everything:

Install the Windows Azure NPM module

The azure npm module provides the basis for all of the Windows Azure stuff we’re going to do with node.js. It includes all of the support for using blobs, tables, service bus, and service management. It’s even open source. To get it, you just need to cd into the directory you’re using and run this command:

npm install azure

After you have the azure module, you’re ready to rock.

The Backend

The backend part of this project is a worker role that accepts HTTP Post messages from the Instagram API. The idea is that their API batches messages, and sends them to an endpoint you define. Here’s some details on how their API works. I chose to use express to build out the backend routes, because it’s convenient. There are a few pieces to the backend that are interesting:

Use nconf to store secrets. Look at the .gitignore

If you’re going to build a site like this, you are going to need to store a few secrets. The backend includes things like the Instagram API key, my Windows Azure Storage account key, and my Service Bus keys. I create a keys.json file to store this, though you could add it to the environment. I include an example of this file with the project. DO NOT CHECK THIS FILE INTO GITHUB! Seriously, don’t do that. Also, pay close attention to my .gitignore file. You don’t want to check in any .cspkg or.csx files, as they contain archived versions of your site that are generated while running the emulator and deploying. Those archives contain your keys.json file. That having been said - nconf does makes it really easy to read stuff from your config:

// read in keys and secrets

nconf.argv().env().file("keys.json");

var sbNamespace = nconf.get("AZURE_SERVICEBUS_NAMESPACE");

var sbKey = nconf.get("AZURE_SERVICEBUS_ACCESS_KEY");

var stName = nconf.get("AZURE_STORAGE_NAME");

var stKey = nconf.get("AZURE_STORAGE_KEY");

Use winston and winston-skywriter for logging

The cloud presents some challenges at times. Like how do I get console output when something goes wrong. Every node.js project I start these days, I just use winston from the get go. It’s awesome because it lets you pick where your console output and logging gets stored. I like to just pipe the output to console at dev time, and write to Table Storage in production. Here’s how you set it up:

// set up a single instance of a winston logger, writing to azure table storage

var logger = new winston.Logger({

transports: [

new winston.transports.Console(),

new winston.transports.Skywriter({

account: stName,

key: stKey,

partition: require("os").hostname() + ":" + process.pid,

}),

],

});

logger.info("Started wazstagram backend");

Use Service Bus - it’s pub/sub (+) a basket of kittens

Service Bus is Windows Azure’s swiss army knife of messaging. I usually use it in the places where I would otherwise use the PubSub features of Redis. It does all kinds of neat things like PubSub, Durable Queues, and more recently Notification Hubs. I use the topic subscription model to create a single channel for messages. Each worker node publishes messages to a single topic. Each web node creates a subscription to that topic, and polls for messages. There’s great support for Service Bus in the Windows Azure Node.js SDK.

To get the basic implementation set up, just follow the Service Bus Node.js guide. The interesting part of my use of Service Bus is the subscription clean up. Each new front end node that connects to the topic creates it’s own subscription. As we scale out and add a new front end node, it creates another subscription. This is a durable object in Service bus that hangs around after the connection from one end goes away (this is a feature). To make sure sure you don’t leave random subscriptions lying around, you need to do a little cleanup:

function cleanUpSubscriptions() {

logger.info('cleaning up subscriptions...');

serviceBusService.listSubscriptions(topicName, function (error, subs, response) {

if (!error) {

logger.info('found ' + subs.length + ' subscriptions');

for (var i = 0; i < subs.length; i++) {

// if there are more than 100 messages on the subscription, assume the edge node is down

if (subs[i].MessageCount > 100) {

logger.info('deleting subscription ' + subs[i].SubscriptionName);

serviceBusService.deleteSubscription(topicName, subs[i].SubscriptionName, function (error, response) {

if (error) {

logger.error('error deleting subscription', error);

}

});

}

}

} else {

logger.error('error getting topic subscriptions', error);

}

setTimeout(cleanUpSubscriptions, 60000);

});

}

The NewImage endpoint

All of the stuff above is great, but it doesn’t cover what happens when the Instagram API actually hits our endpoint. The route that accepts this request gets metadata for each image, and pushes it through the Service Bus topic:

serviceBusService.sendTopicMessage("wazages", message, function (error) {

if (error) {

logger.error("error sending message to topic!", error);

} else {

logger.info("message sent!");

}

});

The Frontend

The frontend part of this project is (despite my ‘web node’ reference) a worker role that accepts accepts the incoming traffic from end users on the site. I chose to use worker roles because I wanted to take advantage of Web Sockets. At the moment, Cloud Services Web Roles do not provide that functionality. I could stand up a VM with Windows Server 8 and IIS 8, but see my aformentioned anxiety about managing my own VMs. The worker roles use socket.io and express to provide the web site experience. The front end uses the same NPM modules as the backend: express, winston, winston-skywriter, nconf, and azure. In addition to that, it uses socket.io and ejs to handle the client stuff. There are a few pieces to the frontend that are interesting:

Setting up socket.io

Socket.io provides the web socket (or xhr) interface that we’re going to use to stream images to the client. When a user initially visits the page, they are going to send a setCity call, that lets us know the city to which they want to subscribe (by default all cities in the system are returned). From there, the user will be sent an initial blast of images that are cached on the server. Otherwise, you wouldn’t see images right away:

// set up socket.io to establish a new connection with each client

var io = require('socket.io').listen(server);

io.sockets.on('connection', function (socket) {

socket.on('setCity', function (data) {

logger.info('new connection: ' + data.city);

if (picCache[data.city]) {

for (var i = 0; i < picCache[data.city].length; i++) {

socket.emit('newPic', picCache[data.city][i]);

}

}

socket.join(data.city);

});

});

Creating a Service Bus Subscription

To receive messages from the worker nodes, we need to create a single subscription for each front end node process. This is going to create subscription, and start listening for messages:

// create the initial subscription to get events from service bus

serviceBusService.createSubscription(

topicName,

subscriptionId,

function (error) {

if (error) {

logger.error("error creating subscription", error);

throw error;

} else {

getFromTheBus();

}

},

);

Moving data between Service Bus and Socket.IO

As data comes in through the service bus subscription, you need to pipe it up to the appropriate connected clients. Pay special attention to io.sockets.in(body.city) - when the user joined the page, they selected a city. This call grabs all users subscribed to that city. The other important thing to notice here is the way getFromTheBus calls itself in a loop. There’s currently no way to say "just raise an event when there’s data" with the Service Bus Node.js implementation, so you need to use this model.

function getFromTheBus() {

try {

serviceBusService.receiveSubscriptionMessage(topicName, subscriptionId, { timeoutIntervalInS: 5 }, function (error, message) {

if (error) {

if (error == "No messages to receive") {

logger.info('no messages...');

} else {

logger.error('error receiving subscription message', error)

}

} else {

var body = JSON.parse(message.body);

logger.info('new pic published from: ' + body.city);

cachePic(body.pic, body.city);

io.sockets. in (body.city).emit('newPic', body.pic);

io.sockets. in (universe).emit('newPic', body.pic);

}

getFromTheBus();

});

} catch (e) {

// if something goes wrong, wait a little and reconnect

logger.error('error getting data from service bus' + e);

setTimeout(getFromTheBus, 1000);

}

}

Learning

The whole point of writing this code for me was to explore building performant apps that used a rate limited API for data. Hopefully this model can effectively be used to accept data from any API responsibly, and scale it out to a number of connected clients to a single service. If you have any ideas on how to make this app better, please let me know, or submit a PR!

Questions?

If you have any questions, feel free to submit an issue here, or find me @JustinBeckwith